Children all say to their parents at some stage, ‘Tell me a story’. Sometimes they want wild, fanciful and even scary stories; other times it will be about an almost forgotten, distant childhood kept alive by the retelling by their parents.

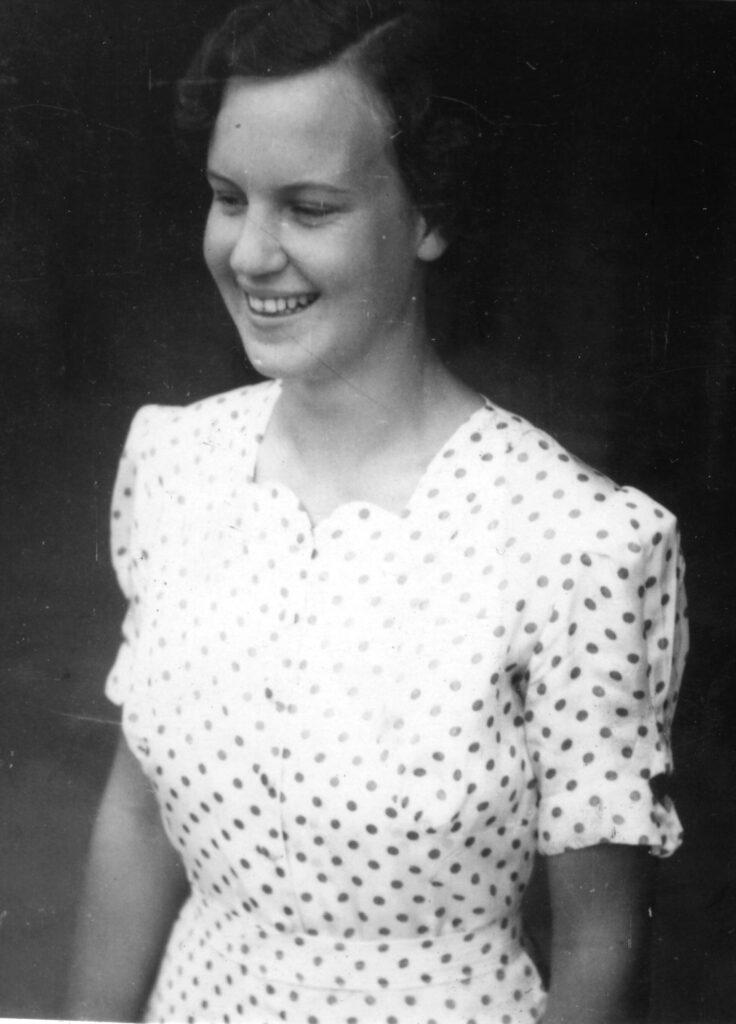

My mother, Jean, would have been ninety-nine today were she still alive. Sweet, outgoing and essentially humble, she always said that her life was ordinary. As a gift for her eightieth birthday, my brother met with her weekly and asked her about her life, recording the conversations. He transcribed these into a book with almost no editing and captured Mum’s extraordinary story: born and brought up in China and India, separated from her parents as a child and then when her parents were interned during the war, working with hundreds of orphans in Hong Kong – all before she turned 30! Her life was far from ordinary, and the captured story reads like a novel. Soon after that, she slid slowly into dementia.

Roy, my paternal grandfather, never told me his story. Like many who returned from World War 1, he kept its horrors to himself. After he died, I discovered from my father that Grandad played an important part in the war on the Western Front at Fromelles and was taken prisoner there. He did not come home to his wife of three weeks for three long, terrible years, but carried for the rest of his life the memories of what historians have sometimes called the worst twenty-four hours in Australian history.

(more…)